When The "Vaccines Cause Autism" Debate Meets The Voice of a Generation

How powerful narratives and numbers can sound legit, even when they're shonky.

I knew when I started this newsletter that one day I’d probably come across some piece of science writing pushing anti-vaccine views. I’d made a promise to myself not to wade into the treacherous waters of vaccines and anti-vax misinformation. It’s a whole other reality, it takes a lot of time and energy to debunk and that’s what many anti-vax groups thrive on.

So it’s with great sadness that today I’m wading into the treacherous waters of vaccines and anti-vax misinformation after reading the latest essay1 by the author Tao Lin, who has (at various times over the last decade) been dubbed the “voice of his generation.”2

The essay, which is about autism, vaccines and environmental toxins, is not really bad science writing as much as it’s bad science wrapped in an interesting, clinical narrative about the author’s own struggles.

It provides a great example of how controversial and poor scientific studies can be used to bolster particular points of view — and how we might recognize when we’re only getting one side of the story.

Let’s get into it.

Last week, the author Tao Lin — an Alt Lit figure I’d honestly never heard of because I’m not really into that kind of writing — published a 7,429 word essay after reading ~140 scientific papers. I know this, because Lin tweeted it, on Sep. 22. It came to my attention via a tweet from The Conversation’s Michael Lucy calling out the bad science.

Lin’s essay traces a path through history and the early research on autism, includes a personal history of his own experiences as an autistic person and then starts to lay the blame for society’s varied illnesses and disease — including autism — on vaccines (aluminium adjuvants, don’t read this) and environmental toxins (glyphosate, don’t read this either).

I found reading Lin’s post just… kind of engrossing, to be honest. I was hooked by the way it wove the deeper history of medicine with the personal, the huge amount of references to other books and ideas, the punchy, sometimes-heavy passages and the stark and clinical presentation of detail and statistics. He details ways he has become “less autistic” by using drugs and meditation.

But to summarize, Lin’s essay is really a treatise on how humans have polluted the natural world and how that pollution is making us sick. Overall, this is not really a controversial thing to suggest. Many great studies, sufficiently powered and adequately controlled, have looked at and continue to look at these issues.3 One in particular, glyphosate — widely found in weed killer — has attracted a huge amount of attention and been linked to numerous conditions, like lymphoma. But Lin goes on to say

“Glyphosate and aluminum may be the current largest factors so far identified in autism”

And I think that’s worth drilling down on.

Human exposure to glyphosate has increased dramatically since genetically engineered crops were introduced in 1994 by agriculture firm Monsanto (which was bought by German biopharma giant Bayer in 2018). Lin focuses much of the latter parts of the essay on glyphosate and segues into an anti-vaccine screed about aluminium adjuvants — and how the two work together to create issues in the brain.

He provides a lot of references in this section which, at first glance, seems to increase the authority, but many of them are poorly-powered studies, authored by “fringe” scientists or rubbished many years ago. Of course, the narrative is presented in such a way this would be difficult to know and actually getting the references and finding them requires opening another webpage, scrolling through the list and then going to Google and trying to hunt down the original paper.

All in all, not great for a reader who might be skeptical buuuuut pretty good if you’re trying to mount a convincing argument and hoping no one runs through your work line by line.

One particular element of the glyphosate/aluminium section hinges on the work of Christopher Exley, a Keele University scientist who has produced studies assessing aluminium levels in the brains of autistic people. These studies have been rubbished by other scientists4 but Lin does not reference the problems with the papers or any other views on them.

This, at best, shows Lin is not across the entire swath of scientific literature (he claims he read about 140 scientific papers to write the essay.5) in the space and, at worst, shows he's deliberately misleading the intended audience of his piece. I can't say which of the two is true but I would point out the essay does rely on a few sources to push it forward, rather than a varied mix.

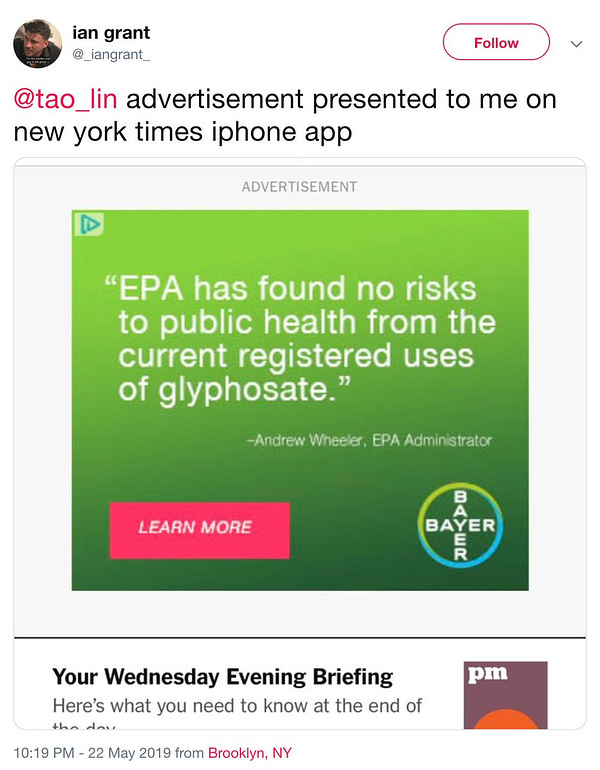

The essay is also at pains to paint corporations, mainstream media and the government as all part of some sort of cabal to prevent the truth from being told. It references a 2019 tweet, below, showing that New York Times ran an advertisement by Bayer that “could be a New York Times headline”:

The account that posted the tweet to Lin no longer exists, but I think it’s interesting to note this advertisement is (judging by the AdChoices logo) likely algorithmically served to the user based on previous browsing activity. Someone who follows Lin’s work and interest in glyphosate being served an ad for glyphosate? Weird!

And while the ad isn’t exactly great (not sure glyphosate should be getting such a free pass in an ad like that) it’s pretty clearly labelled as an advertisement and unlikely to be misconstrued in the way Lin describes.

That’s not to say the media is perfect, especially when it has come to discussions around Monsanto and glyphosate over the years. There are problems there. That’s a whole other thing. But the way Lin frames these arguments and pushes forward his essay is really intriguing to me because it shows just how powerful a narrative can be if you get all your words in the right order.

Why this matters

I think the reason I didn’t want to get into the anti-vax space was because, even as I was writing this newsletter, I could tell just how complex it is to debunk some of these ideas. It becomes more complex when they are referenced as extensively as Lin’s essay is, even if those references often point to poorly-conducted studies, without adequate controls.

Lin might have a strong point about environmental toxins and human health. We do pump a lot of crap into the environment that can’t be good for us. We find microplastics in basically every corner of the world. PFAS, which I’ve written about in this newsletter before, is also dangerous. We come into contact with mercury and lead, at times, in concentrations that destroy us. I mean, asbestos, anyone?

What’s really insidious about this is how the word “studies” is used constantly, weaponized to bring authority and levity to the piece. “Studies” is such a loaded term. I think when we read that word we automatically give it some kind of weight. But analyzing sources is so important — how can we trust what we’re reading, even if it stirs us or reads well?

It’s worth googling a study or an author and seeing what comes up. It’s worth typing a study title into google and establishing its retracted. It’s worth questioning where a piece is published and the argument its making. It’s worth investigating every single company listed in an essay from the New York Times to Children’s Health Defense. But, you know, we don’t have a lot of time. So you can just read bad science writing newsletters like this, I guess.

Stay well-read, friends

What else?

I completely messed up last week’s newsletter and had it sent only to paid subscribers. This email is free. There are no paid subscribers. It went out into the void and was read by one person: Me (3 times, as I frantically tried to understand why it hadn’t been delivered). If you want to read it, you can find it here.

Really enjoyed this piece from Simon Parkin about TikTok, a pawn shop owner and an album of old war photos. Also this, on Lauren Jackson’s return to basketball for the World Cup, was really great and I finally got around to reading a piece in Nature by Dyani Lewis about “what scientists have learnt from COVID lockdowns.”

You can find it in the Mars Review of Books.

The generation is millennials, btw. Referenced in this New Yorker article from 2021 and an older Vice piece, in 2013.

Ie, the ANU’s study into PFAS and human health, for instance. Take a look at how this kind of study is conducted, compared to some of the references Lin has used (ie,

You can find one such rubbishing at RetractionWatch for a major paper of Exley’s from 2018.

I sussed my thesis and found it has 171 references. Thinking about this, I reckon I would have ticked over 1,000 papers in those 3.5 years, easily. That’s about 80k words.