Unless you’ve been extinct since 1936 or living under a mammoth-sized rock, you’ve probably heard a lot about the plan to bring the thylacine — or Tasmanian tiger — back from the dead.1

Reporting on the plan has, mostly, been really good. Many articles have explored the moral, social and ethical obligations of trying to do this, in addition to the feasibility. Some reporting has been a little worse — one-sided, unbalanced or leaning into the hype. And then there’s the social media influencer campaign2…

There are a few good lessons in this story for science journalists and readers of science journalism alike but I want to drill down on two things: Science vs start-ups and those ‘science influencers.’

Let’s go.

First, a brief history of thylacine resurrection: On August 16, US biotech company Colossal announced it was collaborating with — and funding to the tune of $10 million dollarydoos — the University of Melbourne’s plan to de-extinct a thylacine. The University had also received $5 million in philanthropic funding back in March.

The story, which was embargoed by Colossal to drop at 8am ET, hit the web like a freight train. Pretty much every major news site in Australia had it covered in some way, and plenty of specialist science websites and tech publications abroad did too. It featured on panel programs like The Drum and Have You Been Paying Attention? and Andrew Pask, the lead researcher at UniMelb, was interviewed at the desk on The Project, too.

This kind of press is, of course, damn unusual for a scientific funding announcement. For James Webb Space Telescope images? Sure, I expect those on every screen.3 Gravitational waves? Yes, resident space nerds are going to be on your radio and news breakfast programs discussing a recently released paper to bewildered hosts.

However, though it uses science to achieve its goals, with de-extinction work from Colossal we’re not operating strictly in the world of science. We’re operating in the world of start-ups. There’s no paper or basic research to leapfrog off here. There are announcements and announcements for announcements and every time a few million is put into a project, that hits the news. In this world, media attention is paramount.4

It’s been interesting to see how scientists not associated with the project have reacted. Some have called it a ‘fairytale’ or ‘impossible’ or claimed the announcement is ‘more about media attention for the scientists.’

Because, yeah, it is about media attention.

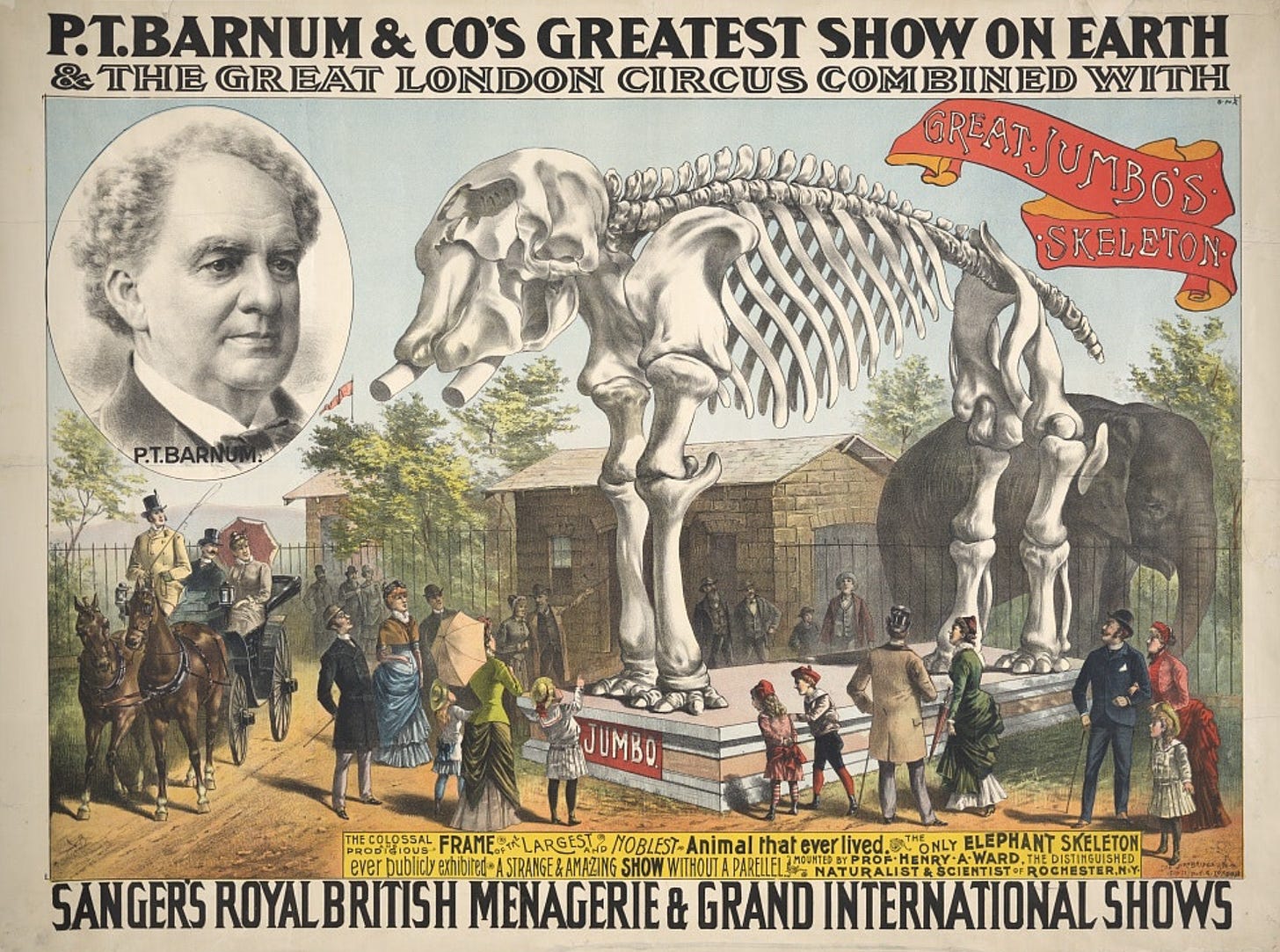

That’s why the news was embargoed. That’s why the researchers were available for interview prior to the announcement. This announcement was for media attention, like every science press release that comes across a journalist’s desk every week. Maybe this one was promising a lot but, you know you’re going to come out and see the old travelling circus if it has the skeleton of the “largest animal that ever lived” on display.

It’s not quite as enticing if it’s just a regular old elephant skeleton, right?

Even so, it’s up to science journalists to take the release, analyse and dig deeper. That definitely happened. What followed in mid-August was a bunch of excellent pieces from specialist science reporters across the web. The headlines might have said “de-extinction” but many stories I read were nuanced, balanced and provided a solid argument against this happening at all. Textbook.

Is this… enough? I don’t know. Are the key messages getting across to readers? I’m not sure. It’s not for lack of trying, though.

Things get more complicated with this story is when we look at where the line between scientific research and start-up spectacle gets drawn — and for what reasons.

Pask is an accomplished marsupial evolutionary biologist. He currently has two active projects5 funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC) to the tune of around $1.2 million. These are unrelated to the thylacine resurrection work, though some of the insights may be useful. The projects are to develop the dunnart as a model for conservation research6 and to determine how changes in DNA might explain how selection, adaptation and evolution works.

So while one of the primary arguments against the project has been “why not preserve the species that already exist today?” … that kind of falls over when you see the UniMelb team are performing the basic research that could help do just that.

The $10 million for “de-extinction” research is additional. The laboratory will be able to support eight new post-doctoral positions with the money — and at least two honours or PhD students each, according to Pask. This is sixteen scientists working and developing skills over the next three or four years. This pipeline of new talent is one of the most overlooked and critical aspects of this project.

If the science is impossible — and it may well be, perhaps it’s even likely that it is — then the science is impossible. The moral, ethical, legal and governmental complications are not something we should look past either. They need to be tackled, today, absolutely. I’ll lead the charge!

But the project isn’t just to bring money in and for the scientists to run off around the world with it? Sixteen young scientists are going to attempt to make this a reality and, even if they can’t, they’ll finish with honours theses or PhDs having learnt marsupial evolutionary biology and physiology and development and so on and so forth. Given the abysmal state of research funding in Australia, well… that seems like a win? And that’s going to become fairly important in a country with one of the worst extinction rates on the planet? To have trained specialists with experience in basic research to carry their knowledge onto new projects?

What is harder to reconcile is the start-up approach crossing over into the realm of science with science influencers. (Scinfluencers? Scienfluers? Sci Flues? Email me what this term is please)

A few publications (inc. The Age and The Guardian) noted influencers had been tapped by Colossal to spruik the new project on Instagram and TikTok. It appears to be quite limited in scope — no more than a couple of sciencey folk with minute long videos — but it’s a little strange. This, of course, has nothing to do with the scientists we just talked about. It’s driven by the Colossal team.

Kristofer Helgen, the chief scientist at the Australian Museum, told the Age he was aware some people had also been paid to tweet about the project after signing non-disclosure agreements. Ben Lamm, Colossal co-founder, told me no one was paid to tweet. I could not find any tweets tagged with the #colossalpartner hashtag, but perhaps it’s more insidious, which would be a real concern.7

Helgen also noted to the Guardian the practice was pretty unusual:

“Instead … we’re seeing a very different corporate approach, which is asking social influencers – who may not know too much about marsupial biology, for example, but have large followings or science-oriented followings – to pump out media that’s positive. This company stands to make money from the publicity.”

It’s definitely weird, but is it any weirder than, say, NASA tapping celebrities and others to get people excited about the Artemis I launch? That only feels a little less weird, to me.

And even as weird as it makes me feel to see the TikToks and Instagrams (and recoil with a visceral “get off my lawn” and shaken fist combo) they aren’t all that bad in explaining the key concepts. Sure, they’re a little overhyped but they’re also clearly marked as partnerships, from what I’ve seen, and don’t go any further than many of the news headlines did. It may be an uncomfortable truth this is the new frontier for science and scientists — but it is. You’ll either join it or be left behind.

There are hundreds (thousands?) of scientists already on TikTok spruiking their own work or doing outreach or sharing preprints that sound cool without really digging into the feasibility or viability or ethics or morality. People who may not be trained in astrophysics or archaeology or paleontology or myriad other science disciplines.

I’d even argue the Australian Museum should be out there making TikToks, right now, that discuss conservation and why the plan is a bad idea.8 And not just that, but also their exhibits and displays, the kind of research they do, the awards they give out and jumping on memes to get the next generation inspired.

Colossal and the UniMelb team have a lot of questions to answer about the long-term feasibility of this project. Science is going to answer some of the major questions. But both scientist and start-up need to be getting out ahead of these questions before their next big media blitz. If they truly can bring a thylacine-like creature back from the dead, if that is “100%” certain, then they can’t wait until it’s developing in the pouch of a mouse-sized dunnart.

The line is already blurring between science and start-up. The worst aspects of the latter shouldn’t inform the former. But where do we draw the line between the two when it comes to social media or media attention and press releases? And why? As this project moves forward, we’re likely to get closer to an answer.

Stay extant, friends.

MORE? I’ve used Midjourney AI to generate headers for this newsletter some weeks but last week, I got called out. Though this is a free newsletter, there are some outstanding issues around AI art and its uses and how it affects, particularly, indie artists. Until it becomes a little more clear on what datasets the AI is being trained and how, I’m going to stick to using Public Domain pieces. You can read a pretty good summation of some artist’s fears in this article by Luke Plunkett at Kotaku.

All the pieces in this weeks piece are from the Public Domain Review and John Gould’s Mammals of Australia.

These weren’t tied to scientific papers, necessarily, but to a calibration of the telescope.

Obviously, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t interrogate the science.

You can find them both at the ARC data portal.

I’ve previously written about this work and why it could be important. De-extinction was a moonshot then…

It would be particularly poor form if there were scientists paid to tweet without anyone knowing.

If they aren’t already? I can’t find an account.