What The **** Is The Point Of Us Then?

Are we better than the machines or not?

Every time I open my horror-supplying doom-rectangle and stare into the void, I see countless terrors. A genocide; livestreamed. Fascism; unchecked and growing. Vitriol and division, racism and sexism. Terrible Philadelphia Eagles playcalling! I should not unlock the device, but I unlock the device again and again.

Amongst all those horrors, I also run into very bad science reporting. I can’t speak to much of the above (besides noting Philadelphia look terrible right now) but I can speak to bad science reporting. Lately, my face feels constantly contorted into the same shocked expression painted on Caravaggio’s Medusa. Almost daily, I see a terrible piece of science journalism.

I started this project, originally, to write about that stuff. But it was difficult. Because one of the things I wrestled with was the idea that I’d be punching down in some way; critiquing other science journalism from the position I’m in — President of an Association, for a long time a full-time, in-house reporter — would be unfair or unhelpful. It might also, as a freelancer, be detrimental. Why would a publisher give me a chance to write science journalism if they saw I was just constantly mad at science journalism?

Other questions: Do we need a space where a science journalist can air complaints or issues with science journalism? Would that make the craft better at a time when there are less jobs, less opportunities are more division than ever? Would calling out bad science journalism improve it or just get me into an internet shit fight I have no energy to continue?

So when the opportunity to Post or Not Post arose (and it arose often), I have mostly erred on the latter side. Typically, instead, I would flick a maddened text to the Group Chat, release some tension, get on with the day. Or, maybe, every now and again, unbridled rage has spilled over into a slightly aggressive post on Bluesky, or a bristling Discord post, or an overly-polite email to ask WHAT THE FUCK ARE YOU DOING?

Lately, my feeling has changed. Poor quality science journalism keeps stacking up and it can have real consequences. While this was, perhaps even just a few years ago, a bit of a problem — undermining trust in science, splintering belief, allowing conspiracy to flourish, creating parallel universes where evidence doesn’t matter — it has now become a full-blown, doomsday-level event, a continent-killer asteroid just inches from the Earth’s surface1

I can give you the full .pptx on this (if you have an hour or so and pay me for the time because my rent is increasing this January god damnit) but the thesis is basically: The vast majority of science reporting that appears in the press — the stuff that most people see in papers, online, social media, on the radio and on telly — comes via press release, from influential universities and via the major science journals.

In the best case, the journalist has spoken to the authors of a scientific paper, and peers in their field, read and understood the scientific paper and contextualised the findings with other experts in the field. There are outlets, and journalists, that approach science journalism this way. This, the Good Stuff, is getting harder to find.

Then, in the worst cases — becoming increasingly common — science stories are just rewritten from press releases. Well-meaning journalists, both generalists and science journalists, attempt to cover science without ever attempting to read the paper, understand the data, speak to other experts or accurately reflect the conflicts of interest.

This slow degradation of Very Good Stuff has been treated with a level of apathy from other science journalists. And I get it. There’s just so much to do. There’s so few resources. And I think we’ve generally believed the Good Stuff will rise to the top. But antagonistic algorithms actively promote the Good Enough or Outright Bad Stuff. Sensationalist, emotional reporting is rewarded with eyeballs and clicks. Decision makers make decisions based on those numbers. And the cycle repeats.

The vast majority of today’s science journalism can not survive if we continue down this path.

The Bad Stuff is at yuuuge risk. It’s about to be swallowed whole by the relentless march of the genAI machinery as Your Good Friends In Corporate :) looks to save money on us pesky, flesh-and-bones workers.

Surely the best way to protect against this is double down on the stuff genAI can’t do. If we’re not going to do The Good Stuff, the Important Stuff, the Hard Stuff, the Challenging Stuff… then what the fuck is the point of us? What is the point at all?

I sound defeated because I feel defeated.

Just this week, a study on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) was published in Springer Nature’s Journal of Translational Medicine. The title of the study was this repulsive-to-regular-humans mumbo jumbo:

Development and validation of blood-based diagnostic biomarkers for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) using EpiSwitch® 3-dimensional genomic regulatory immuno-genetic profiling

[Part 1/1429 of why you need science journalism: Whomst amongst ust would willingly decide to stare at a wall of text titled in this way when they can either throw on KPop Demon Hunters or jam chopsticks into their eyes instead? Who is actively choosing to read a scientific paper like this outside of the scientific community?]2

This study claims to have developed and validated a blood test that may be able to distinguish patients with ME/CFS from healthy adults via changes in how DNA is folded. The researchers claim these changes (“epigenetic” changes) produce a reliable, consistently identifiable profile in patients with ME/CFS that isn’t seen in healthy people.

That would be significant. ME/CFS is an illness that is not recognised by pockets of the medical community and the basis for ME/CFS is poorly understood. This leads to a lot of stigma and prevents accurate diagnosis. The researchers — many affiliated with a biotech company that developed this test — trade off the controversy that many patients often go undiagnosed to ratchet up the emotion around the research.

And it worked. Given this was published by scientists working in the UK’s University of East Anglia (alongside the company developing this blood test, Oxford Biodynamics), it’s no surprise to see that many UK outlets picked up the story, including Sky News, The Times, Daily Mail, The Independent and — the publication I am going to focus on here — The Guardian.

The Guardian is by no means the only offender here but it’s a major newspaper with millions of readers, among the biggest of the lot here3. I have contributed to its Australian arm multiple times since the beginning of 2024. I would imagine that if a freelancer turned in a piece like this to the editors I work with, that they would scoff at it. I have been in awe of some of the work from its Australian health, science, environment and tech reporters. So it’s really disappointing to see how this story was handled.

This story shouldn’t have been on the Guardian in the way it was. It starts with the University of East Anglia (UEA), which should cop some heat for its press release titled “Revolutionary blood test for ME / Chronic Fatigue unveiled”. In the text, it also used the word “breakthrough”…

That’s overselling the study’s findings, at least according to other experts in the field. There’s commentary in Nature, for instance, that urges caution and highlights significant deficiencies with the experimental design in the study.

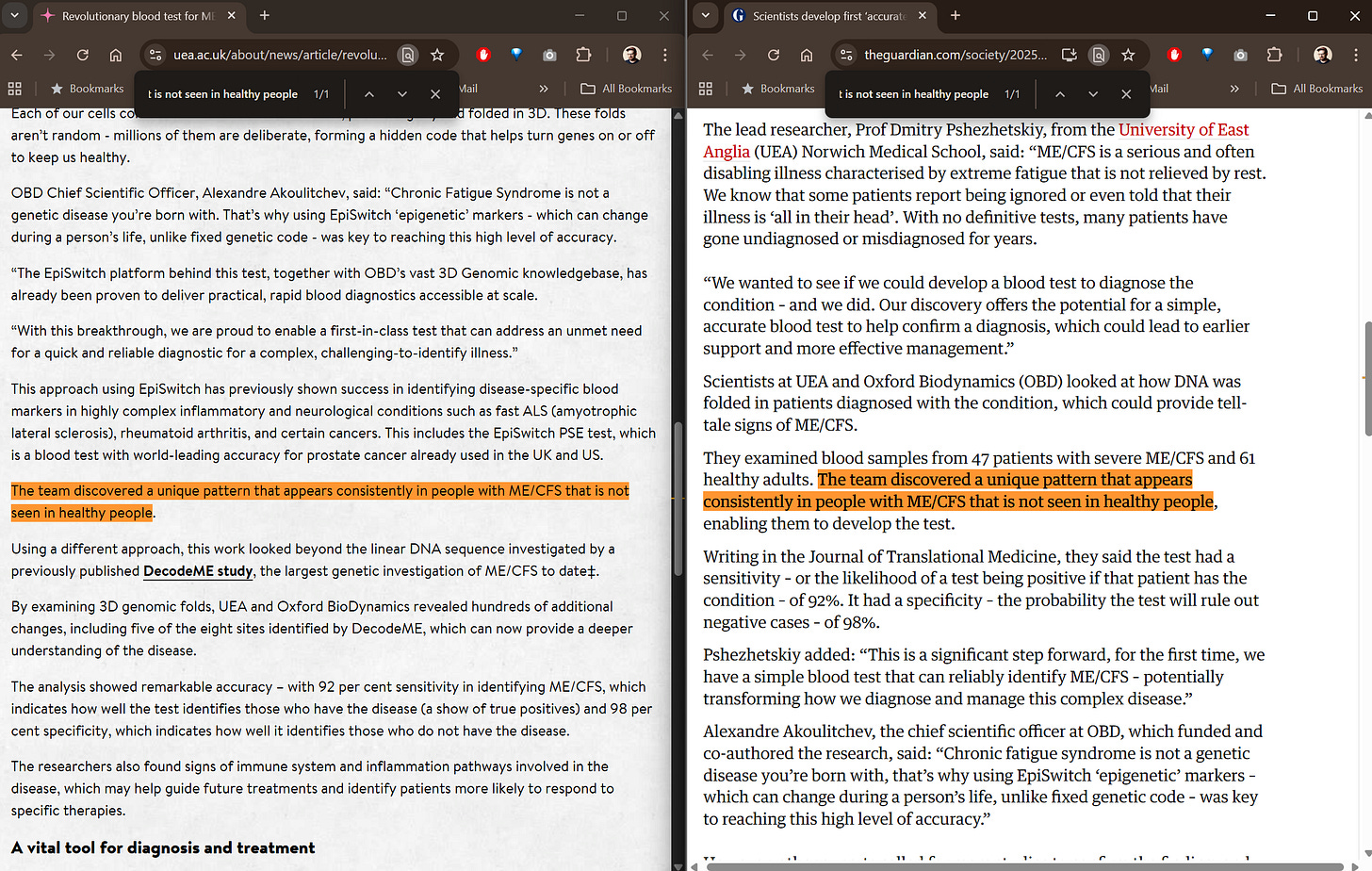

The Guardian didn’t run with a headline or story that featured revolutionary or breakthrough, to its credit, but it appears the outlet did not speak to any of the researchers associated with the paper. Instead, it has used quotes that were provided in the UEA’s press release. It also appears to have, in at least one passage, directly copied the content of the press release.

There’s not a lot of ways to write this particular statement, but I’d hope there would be some differences between the press release and a journalist’s copy.4

The framing is also problematic. The headline at the Guardian is “Scientists develop first ‘accurate blood test’ to detect chronic fatigue syndrome” which, again, oversells the findings. The Guardian is aware of this because it did have commentary from an outside expert.

In its final two paragraphs, it features commentary from Chris Ponting, a researcher in ME/CFS at the University of Edinburgh, who noted some of the claims were “premature” and provided this quote:

“This test needs to be fully validated in better-designed and independent studies before it is considered for clinical application. Even if validated, the test will be expensive, likely (about) £1,000.”

That brings some balance to the content of the article, but it also reveals how much But Ponting’s quote was not obtained by the Guardian journalist, either. It was obtained by the UK Science Media Centre. The UK SMC is a useful resource and it’s reasonable to reuse the quotes it obtains but this suggests the entire story required little to no effort from the reporter — no emails sent, no phones called, no discussions had, no data observed… perhaps, no papers even read?

And so I ask: What is the point?

Science journalism can — and should — be a barrier against misinformation. It should be careful, cautious, considered. The bare minimum should be picking up the phone and speaking to researcher. Maybe you can get away with this kind of reporting if you’re writing about a new black hole being discovered, but when it comes to an illness like this, ignoring the expert opinions of a swath of scientists? Nope. It’s not good enough.

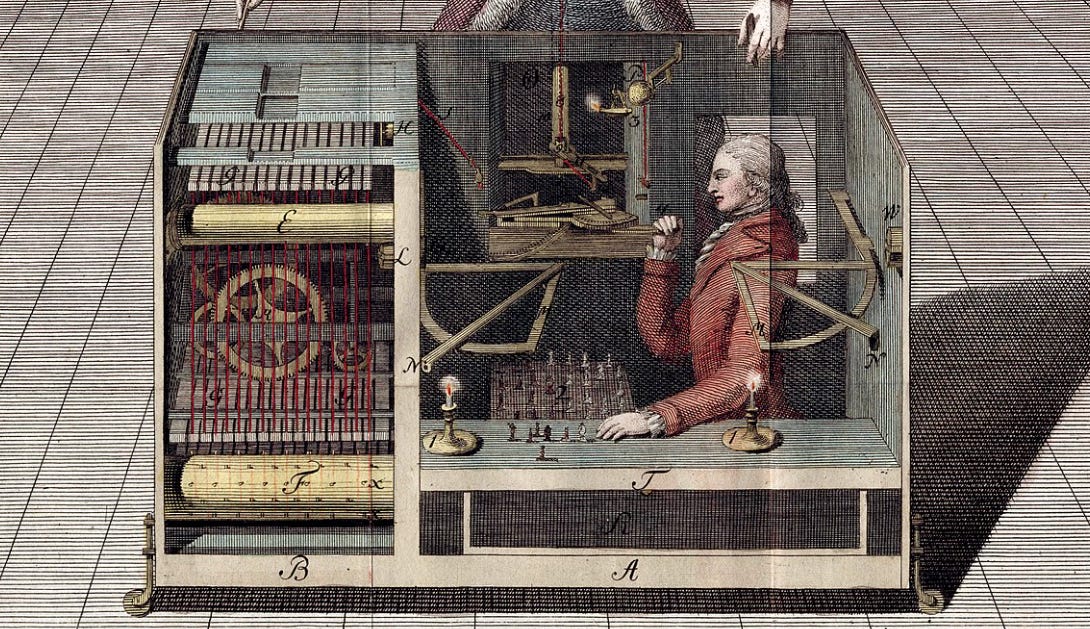

What is the point of science journalists if we’re just recapitulating the content that is in a press release without interrogating it? If we are little more than the machines we are so terrified of, what is the point. We are as good as a Mechanical Turk: Our science journalism seems written by the machines, and yet, there’s us, plucking the keys.

I really don’t want to crucify a specific journalist because there are structural, organisational and business interests at play, all conspiring to place pressure on every one working in media. It’s hard to keep up with changing algorithms, tastes, audiences.

But the standard we walk past is the standard we accept. It was once just a frustration. It’s become a threat to survival.

If this is the standard, then niche, specialised science journalism as we have been performing it is in significant strife. Generative AI will do this exact thing, if it can’t already. You will be able to throw in the press release, the scientific paper and ask the text predictor to shit out these kinds of stories. Again: What is the point of us?

Please, astrophysicists, do not explain to me the weird physics that would be occurring at that distance, nor how long such a period would last etc etc.

This is not to say members of the public wouldn’t read it, especially in the ME/CFS community, which has long sought a valid diagnostic test for the illness. But this is not a fun title guys!!

Is it the biggest? Maybe. It takes a lot of energy to look up these figures and they’re always a little wonky.

FWIW it seems like The Independent ripped the exact same sentence. I asked the author of the Guardian piece about their process, but did not hear back. It’s also the weekend, so there’s that. I will happily update this if I hear more.